Letter from a Bookworm Number 12

30/6/2025

Dear Fellow Bookworm

It has been a week for dipping into lots of different books, starting some and reading odd chapters of others. On the fiction front, I am enjoying Yael Van Der Wouden's 'The Safekeep' particularly, with its intriguing initial set up and sharply drawn characters. The dialogue is especially effective. On the non-fiction side, I have been equally thrilled and frustrated reading 'Why Liberalism Works' by Deirdre McCloskey. I will make further progress with these and let you know what I think in a future letter. Here is a snap of the books I have been reading for pleasure rather than for work of late:

I have become aware that July 2025 marks the hundredth anniversary of the publication of the first volume of Mein Kampf, which for all is repellent content is surely one of the most consequential books of the twentieth century. Before writing about it, I thought I should get myself a copy in English translation and at least look at some of it. But could I source a copy on Amazon? No. Nothing available, despite the book being in print and apparently orderable from a range of other booksellers. Is this a case of censorship by the world's largest supplier of books? I hope not.

'The Way We Live Now' by Anthony Trollope

This month marks 150 years since this huge novel was first published in June 1875. In my Penguin Classis edition it runs to nearly 800 pages and was the longest book that Anthony Trollope (1815-1882) wrote. He was by this time very well-established and at the height of his abilities. The novel is one that many rate as his best and it remains a superbly enjoyable read. It is intended to be a satire on the way that the upper middle classes conducted themselves in the 1870s, its main themes being the impossibility of reconciling prevalent values and motives. In the main it focuses on money, love and social class, but there are other themes included too, notably prejudice against Jewish and Catholic people which while waning by this time was still very present. There are two superbly portrayed villains in this take in the form of the apparently super-wealthy fraudster Augustus Melmotte and a seriously handsome but utterly selfish and dissolute young rake of a baronet called Sir Felix Carberry who is interested in marrying his daughter for her fortune. They are centre stage, but there are at least a dozen other memorable characters, including three most impressive young women. The plot has a soap opera character, but it retains your interest not least because the writing is so elegant and vibrant. Trollope writes with marvellous enthusiasm, juggling several sub-plots at the same time, drawing his readers in and keeping them on board through exactly 100 chapters. Moreover - and this is what I really like about his writing - everything is completely believable. He never finds a need to stretch credulity. It is a masterly example of an English middlebrow novel of a kind I find delightful. I have read it twice now, and would not be surprised if I give it a third read before my days are out.

'The Cider House Rules' by John Irving

This is another chunkster of a novel hitting a notable birthday this month. Published in 1985, it runs to 700 pages in my paperback edition, and like 'The Way We Live Now' it is a highly engaging page-turner which also manages to be thought-provoking. This novel is set in Maine, principally between the 1920s and the 1950s, and has at its heart a discourse about the merits of terminating a pregnancy when a child is unwanted and would otherwise grow up as an orphan. Abortion was, of course, at this time illegal in America though widely practiced. The book is, though, no polemic. You are left to make your own mind up about the underlying issues while enjoying a rather original and well-told story. The central characters are an eccentric, if well-meaning, doctor called Wilbur Larch, who runs an orphanage located deep in the countryside, and one of the orphans, Homer Wells, who he loves as a son and wants to succeed him. He carries out abortions at the orphanage too, where he is assisted by three (later four) devoted nurses and does battle with a board of governors who keep trying to exercise unwanted oversight. We follow Homer through his childhood, adolescence and early adulthood. In the second half of the book he moves away from the orphanage and starts a new life living with a well-to-do family who run an orchard and cider-making business near the coast. There is also a fantastic secondary character called Melony, another orphan, but one who grows up to have a very different future from Homer. The setting and subject matter make this very memorable. It did, for me, slightly lose momentum in the final hundred pages or so, and there is an element of the plot involving the creation of a fictional identity for an orphan who died as a young child, that I found stretched credulity somewhat. And how many times in a lifetime can someone read 'David Copperfield', 'Great Expectations' and 'Jane Eyre' without getting just a tad bored by them? Some of the metaphors are a little clumsy for my taste and the book also seemed to me to be poorly edited at points. We have a character, for example, in the 1930s referring to his time fighting in 'The First World War' and there is the odd typo too. But the paperback, published by Black Swan, is so lovely to handle with smooth paper and attractive, largish print, that all this can be forgiven. It absolutely deserves its reputation as a modern classic.

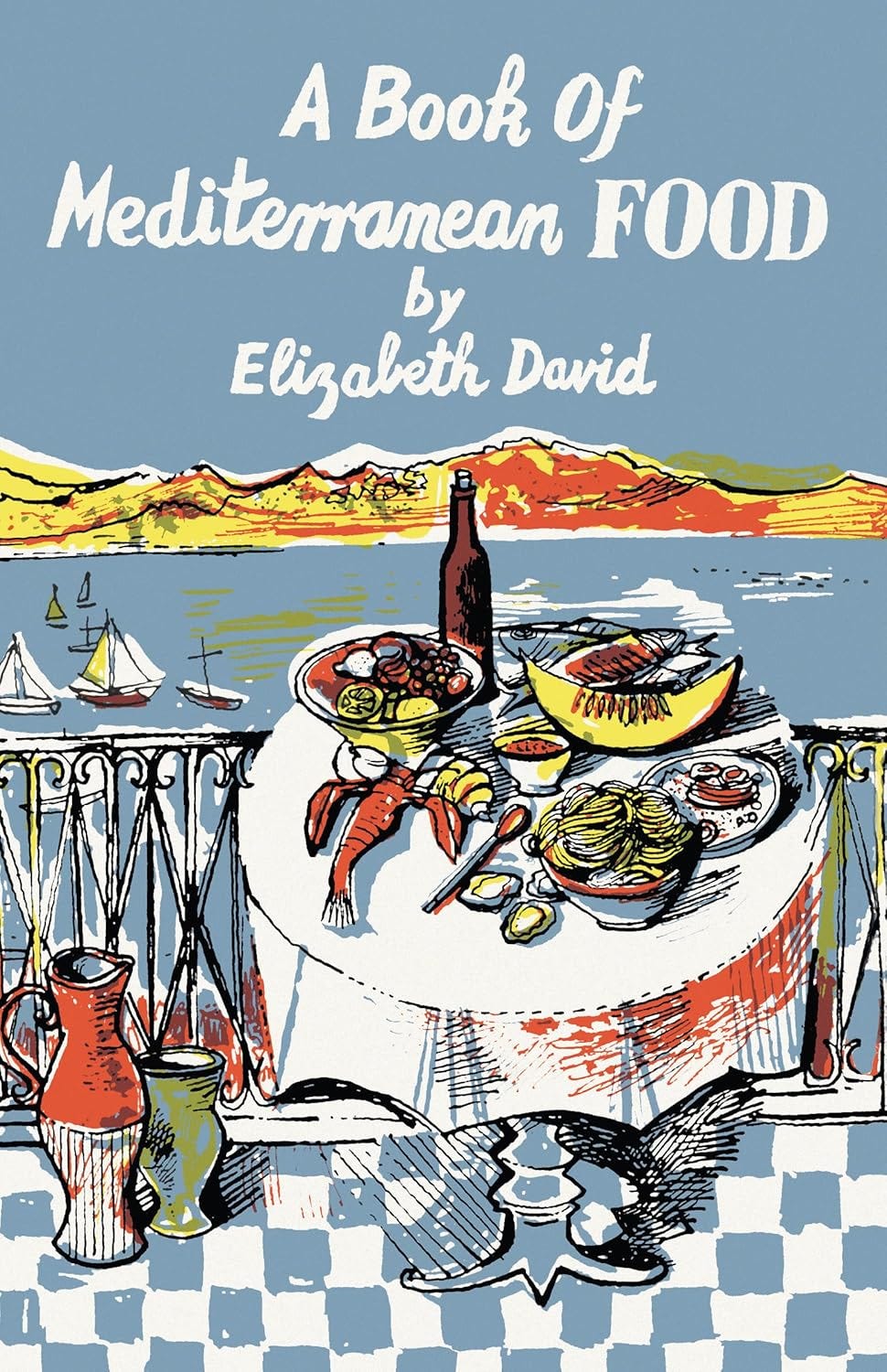

'A Book of Mediterranean Food' by Elizabeth David

This classic and very influential cookery book was published in June 1950 and is thus seventy-five years old this month. It was the first of Elizabeth David's (1913-1992) eight major books (three more were published posthumously), and the one that made her reputation and transformed her life. And what a life it was. She was born into an upper class family, but rebelled against all the values she had been brought up with. She had numerous affairs throughout her life, after spending the late 1930s and early 1940s moving from one country to another, dodging the worst of the fighting in the Second World War. Having cooked nothing at all until her adulthood, she developed a fascination with cooking and started jotting down recipes wherever she went. This sumptuous little book was the product of all that meandering around the Med before and during the war. Returning to a drab London in 1946 she started a career as a food writer and never looked back. When this book was first published, rationing was very much still in place, and her readers will have found it well-nigh impossible to get hold of most of the ingredients she lists. They must thus have been buying the book largely for the purposes of fuelling gastronomic fantasies. And seventy-five years on, it still has a remarkable power to excite the taste buds. Her recipe descriptions are pretty brief in the main. She assumes more than basic culinary competence, but this, along with the passages and quotations she assembles by way of introduction to each section makes the book very readable. The last time I remember having this kind of feeling when reading a book was back in the late 1980s / early 1990s when reading the descriptions of meals in Peter Mayle's splendid 'A Year in Provence' and 'Toujours Provence'. For a longer and meatier read, you could do a lot worse than picking up Artemis Cooper's biography of Elizabeth David entitled 'Writing at the Kitchen Table', published in 2004.

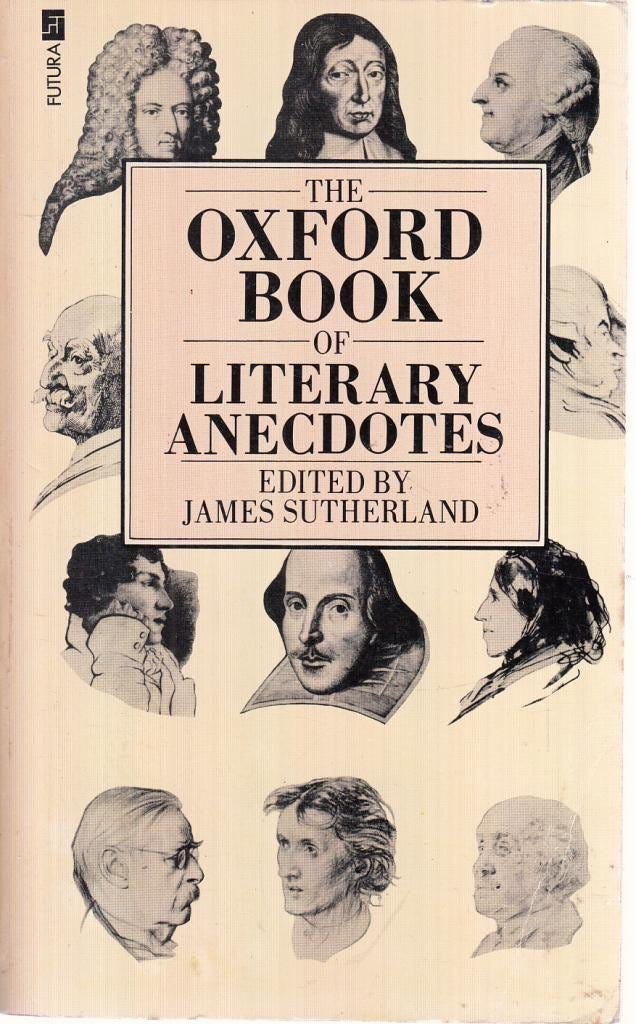

'The Oxford Book of Literary Anecdotes' edited by James Sutherland

This entertaining miscellany was published fifty years ago this month in June 1975. James Sutherland (1900 - 1996), a Professor of English Literature, compiled it in his retirement. The book is less than 350 pages long, and so necessarily omits a great deal. It is also very thin when it gets to the Twentieth Century. Dylan Thomas (1914-1953) is the final entry. Like the wonderful Oxford Book of Humorous Prose edited by Frank Muir and published in 1990, it would surely be the dreamiest of dream jobs to edit an updated version. But it is still great fun to read. I will finish this letter with a section from entry 101, taken from (I presume) 'Letters to His Son on the Art of Becoming a Man of the World and a Gentleman'. This celebrated book was published in 1774 and was notoriously unfavourably reviewed by Samuel Johnson, who had had one almighty bust up with its author extending over several years:

Lord Chesterfield (1694-1773)

I knew a gentleman who was so good a manager of his time that he would not even lose that small portion of it which the calls of nature obliged him to pass in the necessary-house; but gradually went through all the Latin poets in those moments. He bought, for example a common edition of Horace, of which he tore off gradually a couple of pages, carried them with him to that necessary place, read them first, and then sent them down as a sacrifice to Cloacina; this was so much time fairly gained, and I recommend you to follow his example.

With very best wishes

Your Actual Bookworm